Mitosis

Virchow was correct when he concluded that cells arise from others cells, i.e., new cells are born through the division of one cell into two through the process of mitosis. The need for new cells continues throughout our lives, but it is greatest in early life. A fertilized egg divides into two cells, which give rise to four, and those give rise to eight, and then to 16, and 32, and 64, and so on. In a fully grown adult, of course, the rate of cell proliferation is much less, and under normal circumstances, cell division in an adult takes place only when signals indicate the need to replace cells that have been lost, damaged, or worn out.

Source: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/4902908.stm

Differentiation

Another big difference between cells in a growing embryo and cells in an adult is that most of an adult's cells are differentiated - they have become specialized in structure and function. Muscle cells are elongated and contain and abundance of contractile proteins, whereas pancreatic cells are specialized for secretion of digestive enzymes or, in the case of pancreatic beta cells, for the synthesis of insulin. In contrast, the cells in the early morula stage of an embryo (shown below to the left) consists of cells that are totipotent - they have the capacity to divide and give rise to any of the specialized cells in the body. In the adult, however, the replacement of shed or worn out cells takes place by division of somatic stem cells (also called adult stem cells), which are not fully differentiated, but can give rise to only a limited array of cells.

Regulation of Cell Division: Cell Cycle

The diagram to the right summarizes events leading to cell division.

Many cells in an adult are not actively in the process of replicating; this is depicted in the diagram as 'cells that cease division,' also known as the G0 phase or the 'resting phase.' The term 'resting phase' is a misnomer, however, because the cell is actively carrying out its normal specialized functions, and It is only resting in the sense that it isn't actively dividing. If conditions require additional cells, the cell will receive signals that promote cell division. These signals will push the cell to complete the G1 phase (cell enlargement) and proceed to the S-phase, during which DNA is replicated. In the G2 phase the cell prepares for division by increasing in size and replicating intracellular organelles. It then divides through mitosis (the M-phase). In a sense, the critical juncture is the transition from G1 to the S-phase. This transition is carefully regulated by multiple factors, some of which promote the transition. Genes known as proto-oncogenes can be switched on to produce proteins that protein the transition to the S-phase. Counteracting this push to reproduce are genes known as anti-oncogenes (also called tumor suppressor genes) that inhibit transition to the S-phase. The video below provides a short visual summary of these events, known as the cell cycle.

The two videos below summarize the signaling events that regulate the cell cycle and events occurring during the cell cycle.

For more detail see Michael Andreeff, MD, PhD, David W Goodrich, MD, and Arthur B Pardee, MD. Chapter 2 - 'Cell Proliferation, Differentiation, and Apoptosis' in Cancer Medicine, 6th Edition'

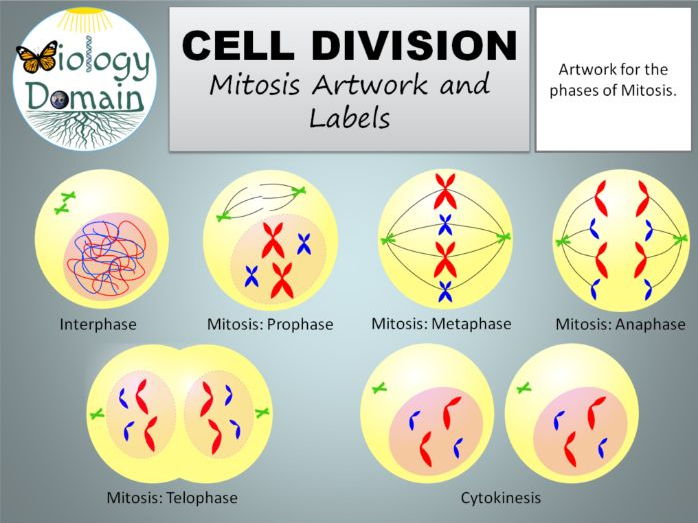

Cell Division Diagram

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is also referred to as programmed cell death. It is an essential process for removing cells that are stressed, damaged, or worn out. It is estimated that over 50 billions cells undergo apoptosis each day in adults. Apoptosis is also carefully regulated through complex mechanisms. Mutations that affect these regulatory pathways have the potential to contribute to carcinogenesis by failing to eliminate abnormal neoplastic cells or by failing to eliminate cells with other mutations that are premalignant. Defects in apoptosis can also confer resistance to chemotherapy, radiation, and immune-mediated cell destruction.

Proto-oncogenes, anti-oncogenes (tumor suppressor genes), and apoptosis, play a central role in understanding the pathogenesis of cancer. In short, mutations and inherited abnormalities can cause these regulatory control mechanisms to become dysfunctional. As you will see, mutations in any of these mechanisms can cause a cell to divide or survive longer than normal, and if multiple mutations affecting these regulatory mechanisms accumulate in a single cell, the cell will have lost all control with respect to cell division. This single cell, dividing repeatedly and without regulation will create an ever expanding clone of cells which will also undergo unregulated cell division. This is the essence of cancer.

Normal Cell Division

The outer layer of skin (epidermis) is about 12 cells thick. Cells in the basal layer (bottom row) divide just fast enough to replenish cells that are shed. When a basal cell divides, it produces two cells. One remains in the basal layer and retains the capacity to divide. The other migrates out of the basal layer and loses the capacity to divide. The number of dividing cells in the basal layer, therefore, stays about the same.

Abnormal Cell Division

The transition to skin cancer begins when the normal balance between cell division/cell loss is disrupted. Basal cells divide faster than needed to replenish the cells being shed, and with each division both of the two newly formed cells will often retain the capacity to divide, leading to an increased number of dividing cells.

This creates a growing mass of tissue called a 'tumor' or 'neoplasm.' As more and more dividing cells accumulate, the normal organization of the tissue gradually becomes disrupted.

Benign tumors (e.g. skin moles, lipomas): abnormal growths that are no longer under normal regulation, but they grow slowly, resemble normal cells, and still have surface recognition proteins that bind them together and keep them from invading or metastasizing.

4 Results Of Cell Division

return to top | previous page | next page

Identify the stages of the cell cycle, by picture and by description of major milestones.

Differentiation

Another big difference between cells in a growing embryo and cells in an adult is that most of an adult's cells are differentiated - they have become specialized in structure and function. Muscle cells are elongated and contain and abundance of contractile proteins, whereas pancreatic cells are specialized for secretion of digestive enzymes or, in the case of pancreatic beta cells, for the synthesis of insulin. In contrast, the cells in the early morula stage of an embryo (shown below to the left) consists of cells that are totipotent - they have the capacity to divide and give rise to any of the specialized cells in the body. In the adult, however, the replacement of shed or worn out cells takes place by division of somatic stem cells (also called adult stem cells), which are not fully differentiated, but can give rise to only a limited array of cells.

Regulation of Cell Division: Cell Cycle

The diagram to the right summarizes events leading to cell division.

Many cells in an adult are not actively in the process of replicating; this is depicted in the diagram as 'cells that cease division,' also known as the G0 phase or the 'resting phase.' The term 'resting phase' is a misnomer, however, because the cell is actively carrying out its normal specialized functions, and It is only resting in the sense that it isn't actively dividing. If conditions require additional cells, the cell will receive signals that promote cell division. These signals will push the cell to complete the G1 phase (cell enlargement) and proceed to the S-phase, during which DNA is replicated. In the G2 phase the cell prepares for division by increasing in size and replicating intracellular organelles. It then divides through mitosis (the M-phase). In a sense, the critical juncture is the transition from G1 to the S-phase. This transition is carefully regulated by multiple factors, some of which promote the transition. Genes known as proto-oncogenes can be switched on to produce proteins that protein the transition to the S-phase. Counteracting this push to reproduce are genes known as anti-oncogenes (also called tumor suppressor genes) that inhibit transition to the S-phase. The video below provides a short visual summary of these events, known as the cell cycle.

The two videos below summarize the signaling events that regulate the cell cycle and events occurring during the cell cycle.

For more detail see Michael Andreeff, MD, PhD, David W Goodrich, MD, and Arthur B Pardee, MD. Chapter 2 - 'Cell Proliferation, Differentiation, and Apoptosis' in Cancer Medicine, 6th Edition'

Cell Division Diagram

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is also referred to as programmed cell death. It is an essential process for removing cells that are stressed, damaged, or worn out. It is estimated that over 50 billions cells undergo apoptosis each day in adults. Apoptosis is also carefully regulated through complex mechanisms. Mutations that affect these regulatory pathways have the potential to contribute to carcinogenesis by failing to eliminate abnormal neoplastic cells or by failing to eliminate cells with other mutations that are premalignant. Defects in apoptosis can also confer resistance to chemotherapy, radiation, and immune-mediated cell destruction.

Proto-oncogenes, anti-oncogenes (tumor suppressor genes), and apoptosis, play a central role in understanding the pathogenesis of cancer. In short, mutations and inherited abnormalities can cause these regulatory control mechanisms to become dysfunctional. As you will see, mutations in any of these mechanisms can cause a cell to divide or survive longer than normal, and if multiple mutations affecting these regulatory mechanisms accumulate in a single cell, the cell will have lost all control with respect to cell division. This single cell, dividing repeatedly and without regulation will create an ever expanding clone of cells which will also undergo unregulated cell division. This is the essence of cancer.

Normal Cell Division

The outer layer of skin (epidermis) is about 12 cells thick. Cells in the basal layer (bottom row) divide just fast enough to replenish cells that are shed. When a basal cell divides, it produces two cells. One remains in the basal layer and retains the capacity to divide. The other migrates out of the basal layer and loses the capacity to divide. The number of dividing cells in the basal layer, therefore, stays about the same.

Abnormal Cell Division

The transition to skin cancer begins when the normal balance between cell division/cell loss is disrupted. Basal cells divide faster than needed to replenish the cells being shed, and with each division both of the two newly formed cells will often retain the capacity to divide, leading to an increased number of dividing cells.

This creates a growing mass of tissue called a 'tumor' or 'neoplasm.' As more and more dividing cells accumulate, the normal organization of the tissue gradually becomes disrupted.

Benign tumors (e.g. skin moles, lipomas): abnormal growths that are no longer under normal regulation, but they grow slowly, resemble normal cells, and still have surface recognition proteins that bind them together and keep them from invading or metastasizing.

4 Results Of Cell Division

return to top | previous page | next page

Identify the stages of the cell cycle, by picture and by description of major milestones.

The cell cycle is an ordered series of events involving cell growth and cell division that produces two new daughter cells. Cells on the path to cell division proceed through a series of precisely timed and carefully regulated stages of growth, DNA replication, and division that produces two identical (clone) cells. The cell cycle has two major phases: interphase and the mitotic phase (Figure 1). During interphase, the cell grows and DNA is replicated. During the mitotic phase, the replicated DNA and cytoplasmic contents are separated, and the cell divides.

4 Results Of Cell Division

Figure 1. The cell cycle consists of interphase and the mitotic phase. During interphase, the cell grows and the nuclear DNA is duplicated. Interphase is followed by the mitotic phase. During the mitotic phase, the duplicated chromosomes are segregated and distributed into daughter nuclei. The cytoplasm is usually divided as well, resulting in two daughter cells.

What You'll Learn to Do

- Identify the characteristics and sub-phases of interphase.

- Identify the characteristics and stages of mitosis.

- Identify the characteristics of cytokinesis.

10.2 The Process Of Cell Division Quizlet

Learning Activities

Name Four Results Of Cell Division

The learning activities for this section include the following:

What Are 4 Results Of Cell Division

- Reading: Interphase

- Reading: Mitosis

- Reading: Cytokinesis

- Reading: The Complete Cycle

- Self Check: The Cell Cycle